Last year I made five drawings of the five people who I consider to be the greatest sports stars of the 20th Century and with typical efficiency I am only now doing anything with them. I love sport more than anything else, I think. Like great music or art, it transcends human experience with a potency far outreaching its remit. But, unlike music or art, it retains a crucial element of total objectivity. There are winners and losers in sport; for all the discussion and for all the postulation there will always come a time when all the bullshit must, through absolute necessity, stop. It is this which appeals to me on such a fundamental level. Elemental, even. I need it.

Choosing five outstanding people from the sporting field is foolhardy in the extreme and invariably shot through with bias, blind spots and flaws. Complaints to the usual place, perhaps. Or, even better, how about making your own list? Creative solutions to internet-based disagreement is surely the way forward. For my choices, I tried to pick five people whose greatness went beyond their particular field of endeavour. They are people who made a wider social impact, through their values, their example or their personality.

I consider them to be five of the most inspirational people the Twentieth Century produced.

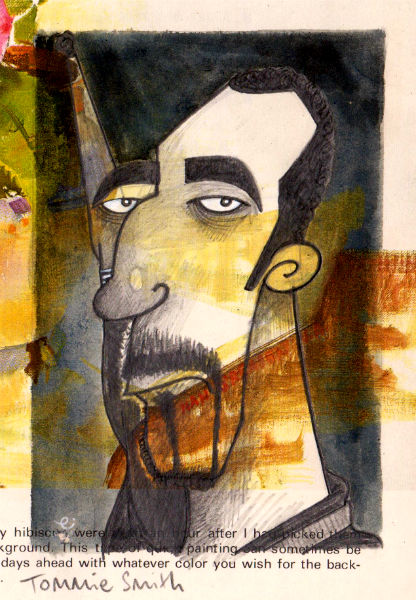

5. Tommie Smith (1944-) - Athletics

Tommie Smith crystallised an entire movement in one single perfect moment. On 16th October 1968 at the Mexico City Olympics, he won the 200 metres sprint in 19.83 seconds. It was an heroic enough performance as it stood: he had been nursing a hamstring injury through the heats and his display in the final was astonishing, the first time that 200 metres had been officially run in under twenty seconds in human history.

Quite rightly, however, Smith is better remembered for what he did on the podium. 1968 had been a year of tumult. In his homeland, it had seen the assassination of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy and the worsening of the conflict in Vietnam. The Civil Rights struggle was far too deeply ingrained to be solved simply by recourse to legislature and racial tension remained a tinderbox across the United States. As for the rest of the world, similar life-and-death struggles for recognition, for freedom and for human rights also raged: Northern Ireland, Warsaw, The Prague Spring, student uprisings in France and West Germany; the continuing stain of Apartheid in South Africa, as well as continuing tension in Israel and Palestine.

Tommie Smith's black gloved raised fist salute was seen as being a symbol of black power and association with the nascent Black Panther movement. In truth, it represented support for everything that is good and just in a year that had, at times, looked set to spiral out of control. Even if in the moment he, silver medallist Peter Norman of Australia and Smith's American teammate John Carlos may have not realised what an epochal gesture they had made, nearly 50 years on it remains the single most staggeringly eloquent reminder of sport's social potency.

Of course, Smith's reward was to be canned. Both he and Carlos were immediately sent home from the Olympics and made pariah by a significant proportion of American society. The following year, Smith moved into American Football, playing two games for the Cincinnati Bengals before becoming both a sociology teacher and an athletics coach at Oberlin College, Ohio.

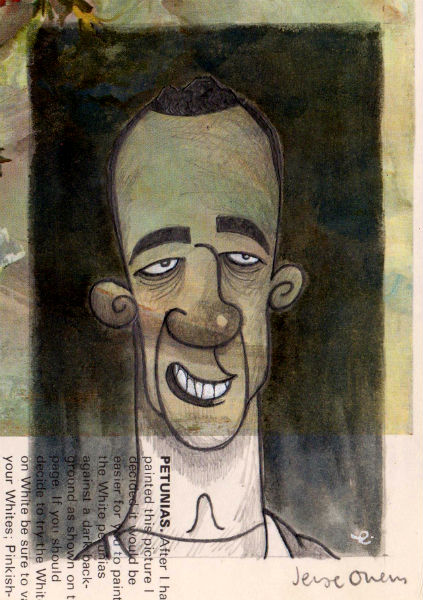

4. Jesse Owens (1913-1980) - Athletics

Jesse Owens was one of the greatest track athletes in history. During the 1935 Big Ten athletics meeting at Ann Arbor, Michigan, he broke three world records within 45 minutes. The following year, he won four gold medals in the 100 metre sprint, 200 metre sprint, 4x100 metre sprint relay and long jump at the Berlin Olympics.

Owens never set out to be a hero or a warrior for social justice. Both things just sort of caught up with him, even when nothing else could. He remains the ultimate fly in the ointment, the most celebrated up yours to the most insidious and evil political regime of modern human history. Adolf Hitler had, of course, designed the Berlin Olympics to be as carefully choreographed a love letter to the innate superiority of his Aryan supermen as any sporting event could be. But he had not reckoned on the basic truth of the forces at work in the sporting arena. 1936 was Owens' time and he would not be - could not have been - denied.

Much has been made of the Fuhrer's avoidance of Owens following his Olympic success. Debate still continues as to whether or not this was the result of prior engagements, a desire to not be caught out in an impending rainstorm or his virulent racism. The possibility even remains that the Nazi leader did seek out and congratulate Owens but that it was subsequently hushed up. The fact remains that Owens' feats were all featured in Leni Reifenstahl's state-funded 1938 film of the event, Olympia, whilst at home he remained a second-class citizen. It is this frequently ignored story which speaks with the greatest volume about the legacy of Jesse Owens, a campaigner for civil rights and social justice. He always maintained that it was not Hitler who snubbed him but his own President. "[He] didn't even send a telegram".

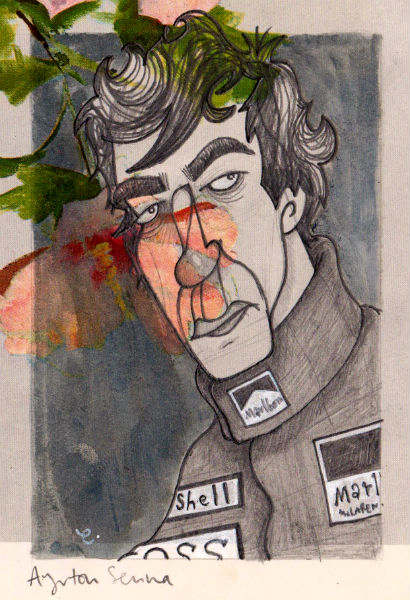

3. Ayrton Senna (1960-1994) - Motor racing

Ayrton Senna was the fastest racing driver who has ever lived. He drove like the devil was after him and he was trying to get away. And as fanciful a narrative as that sounds, the man himself would leave you in some doubt as to whether or not it was what was at stake. There are few people possessed of the kind of single-minded dedication, control and ability to achieve all that Senna did in his brief life, fewer still able to articulate it in quite the same mesmerising way that he did: all the more remarkable if you consider that he was often doing so in a second language.

The winner of 41 Grands Prix, three Formula 1 World Championships and 65 pole positions - the latter a record that it took even Michael Schumacher nearly a hundred additional career races to overhaul - Senna's numbers remain impressive but, as is the nature of many statistics, are slowly being subsumed by history. What will not go away is the story. Senna's electrifying presence transfixed the motor racing world; Formula 1 was Ayrton Senna and to set out to conquer it meant beating him. What will never go away is the footage. Some of it shows him doing things which are devious, questionable or downright reprehensible, all reminders of the fundamental flaws that reside within human beings. These were foes to overcome all as real as Alain Prost, Nelson Piquet, Nigel Mansell or Michael Schumacher. What will never go away is the sight of a man propelling a racing car along at a speed at which his rivals were either unable or unwilling to match.

Senna was a remarkable man. Born of considerable privilege and wealth, he nevertheless remains nothing less than a hero to millions of his disenfranchised and poverty stricken Brazilian countrymen. Clearly flawed and prone to behaviour on track so nefarious it could probably have been tried in a court of law, he remains a hero to every journalist and motorsport fan, one whose legacy grows with each passing year. Had he survived the crash in the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix which claimed him, he could well have been the President of Brazil by now. Or of the United Nations. He may even have been able to swing Pope. To assume anything less of Ayrton Senna always was to be confounded by him.

2. Billie Jean King (1943-) - Tennis

So much of the story of Twentieth Century sport, as with its history, is entangled with the story of race that it is easy to forget that the battle for equality was never just confined to the colour of a person's skin. Women's rights and LGBT rights were - are - just as defining and active a social battleground. Billie Jean King was a pioneer, a leader and a spokeswoman; a brilliant competitor who could have made all her most telling points on the court but chose to speak out off it as well. Moreover, she still is and still does all of these things.

Much is made of her participation in the famous Battle Of The Sexes tennis match, an event between the top female player of the day and Bobby Riggs, the 1939 Wimbledon singles champion who, at 55-years old believed he was still the match of any modern female player. King disabused him of this notion, defeating him comfortably 6-4, 6-3, 6-3. But in reality this was just a spectacle for the television and a silly old fool getting his comeuppance. Billie Jean King is better remembered for the way she lived her life day to day, a fact summed up by her belief that her most famous match's key virtue was getting people interested and enthused about the sport of tennis.

As a player she was an indefatigable competitor. Combined with a longevity rare in such a high impact sport - her career spanned four decades and lasted 24 years - it makes the case for her inclusion on any list of sporting greats on a statistical basis alone. What truly sets King apart for me is her bravery. It takes considerable courage to choose to continually put your head above the parapet because it is the right thing to do, especially when you are successfully operating in an arena which would make anyone quite able to happily and quietly feather their nest ready for a peaceful retirement. King refused to stand down; on the issue of professionalism in tennis, on the issue of equality for women, or on the issue of the acceptance of homosexuals into society. To this day, if Billie Jean speaks openly on any subject, we had better all be listening.

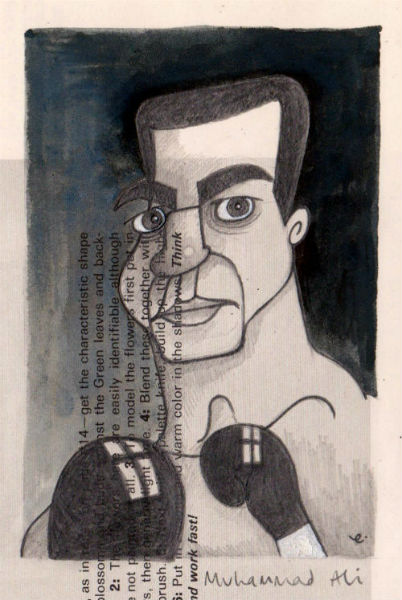

1. Muhammad Ali (1942-) - Boxing

Muhammad Ali is the greatest. We have no excuse for this coming as a surprise as he has been telling us all for decades. It is perhaps to his greatest credit that the scale of his achievement - as a sportsman and as a human being - was such that it was nevertheless still surprising.

No other sporting figure has ever blurred so many social boundaries. He was both of our time and for all time; initially just a boxer, his extraordinary personality made him a star at a time in America where black people were supposed to know their place. Ali stood up and was counted. When this, as it inevitably would, made him enemies he stood louder and prouder. When they took away what was rightfully his he won it back in such impossibly heroic circumstances that it would be dismissed out of hand as a film treatment as simply too unbelievable.

Ali is a continual reminder to me that the search for a higher power is best attempted by looking around you. A glimpse into the eyes of Ali, even now as a frail man broken by disease and dulled by age, leaves me in no doubt as to his other-worldly power to inspire greatness in those around him. There will never be another sportsman who so unifies as many disparate sections of human society as Muhammad Ali. The greatest tribute of all is that, principle among the reasons for this is that Ali existed in the first place.

The five pictures that illustrate this piece are available to buy for £25 each, or £125 for the full set (including Pelé, who didn't make the cut). If you are interested, drop me a message on Facebook or send me an email.

Wednesday 30 March 2016

Tuesday 29 March 2016

Disaster Film Olympiad - Volcano

Los Angeles is a fascinating place. Most of the turbulence that afflicts the city is social - gang violence, racial tension, pro-footballers murdering their wives and getting away with it, etc. - but the potential for far a more elemental catastrophe lurks under every crib, pimp wagon or Ben Affleck's house. The San Andreas fault is responsible, the meeting of the Pacific and North American continental tectonic plates. It makes coastal California ripe earthquake territory and when they strike, they tend to be the sort of earthquakes that do more than rearrange your gnomes.

Of course, Los Angeles is also the home to the American film industry and there is nothing Hollywood enjoys more than occasionally reminding itself that it could at any moment be naught but a smoking crater in the ground, just like Kevin Smith's house. It's all part of that particular deal with the devil that movie stars make with their conscience as the man arrives with the next lorry load of money.

Volcano was released in 1997, part of the brief pre-millennium disaster film renaissance which also saw us clenching our buttocks through Dante's Peak, Twister, Armageddon and Deep Impact. Also notable to anyone who might perhaps be endlessly watching disaster films for no real reason is that the director was Mick Jackson, the Briton who made Threads. Fortunately, Volcano is nowhere near as brutal. Although I don't live in Los Angeles, so maybe it is. The fact that John Travolta potentially considers Volcano to be more frightening than Threads is the take home portion from this paragraph.

Anyway, the earthquake that I had been warning everybody could happen in Los Angeles happens. Our hero, Mike Roark of the city's Emergency Management Committee, puts aside his much-needed family holiday to make sure nothing dreadful has happened: one of the Os in the Hollywood sign may have fallen over, for instance, or Warren Beatty's toilet might be leaking. His decision has long-reaching consequences for some of the city engineering workers, who are cooked to death while inspecting a storm drain. This is an unlikely thing to happen, but Roark takes it in his stride. Roark is an easy man to have sympathy towards. He's middle-aged and craggly, gruff and curt yet possessed of an undeniable twinkly oaky Southern charm. He is a bit like Tommy Lee Jones, so the film's casting director secured something of a coup when they acquired the services of Tommy Lee Jones to essay the role.

The itch in Roark's knickers is Dr. Amy Barnes, a geologist. Being a geologist is comfortably one of the most genuinely perilous jobs that one can have while still being excruciatingly boring conversation at a dinner party, a dichotomy which tends to make them peculiarly strident people. Barnes is convinced that the earthquake has caused the formation of a volcano right under the centre of the city. Roark is sympathetic to these concerns, but he can't just start throwing tax payers' money around without evidence. Evidence that Barnes, to her own frustration and no doubt that of the people who have to talk to her at her friends' dinner parties, is unable to gather.

Fortunately, Barnes has a key ally in her quest: Mother Nature. The volcano that she had been predicting to everyone could volcano erupts right under the La Brea tar pits, causing hundreds of dollars worth of damage to the fibreglass mammoths and also pumping boiling lava all over the place. Wilshire Boulevard, traditionally given over to being the main arterial road for the largest city in California, becomes a regular shit show of burning vehicles, stuck underground trains and fifth degree burns. It's a lawsuit waiting to happen. To her credit, Dr. Barnes continues to work for the good of the Angelenos, where most of us would take to the highest vantage point immediately available and look smug.

There are two ways that this sort of film can go: they either deal with a pre-existing adversarial relationship being reconciled in the crucible of extreme circumstance, or the nascent union between two people being thrown together by events. Volcano is the latter and if the sex is as impressive as Roark and Barnes' teamwork, there may yet be further earth tremors in southern California. Using carefully placed detonations of explosive devices, they manage to channel the lava flow through the city's network of subterranean tunnels and into the Pacific Ocean where it would presumably solidify and form a place even drier, hotter and more exclusive than Los Angeles itself, much to the chagrin of the Hollywood elite.

I don't know enough about volcanology to know whether any of this exotic bill of fayre is likely or even possible, but I know enough about disaster films to say that this is a perfectly serviceable one. It ticks all of the traditional generic boxes - relationships are explored and developed, people are roasted to a crisp and the special effects department get to just go nuts - as well as retaining its own personal charm. Volcano gets SIX out of ten Disaster Points.

Of course, Los Angeles is also the home to the American film industry and there is nothing Hollywood enjoys more than occasionally reminding itself that it could at any moment be naught but a smoking crater in the ground, just like Kevin Smith's house. It's all part of that particular deal with the devil that movie stars make with their conscience as the man arrives with the next lorry load of money.

Volcano was released in 1997, part of the brief pre-millennium disaster film renaissance which also saw us clenching our buttocks through Dante's Peak, Twister, Armageddon and Deep Impact. Also notable to anyone who might perhaps be endlessly watching disaster films for no real reason is that the director was Mick Jackson, the Briton who made Threads. Fortunately, Volcano is nowhere near as brutal. Although I don't live in Los Angeles, so maybe it is. The fact that John Travolta potentially considers Volcano to be more frightening than Threads is the take home portion from this paragraph.

Anyway, the earthquake that I had been warning everybody could happen in Los Angeles happens. Our hero, Mike Roark of the city's Emergency Management Committee, puts aside his much-needed family holiday to make sure nothing dreadful has happened: one of the Os in the Hollywood sign may have fallen over, for instance, or Warren Beatty's toilet might be leaking. His decision has long-reaching consequences for some of the city engineering workers, who are cooked to death while inspecting a storm drain. This is an unlikely thing to happen, but Roark takes it in his stride. Roark is an easy man to have sympathy towards. He's middle-aged and craggly, gruff and curt yet possessed of an undeniable twinkly oaky Southern charm. He is a bit like Tommy Lee Jones, so the film's casting director secured something of a coup when they acquired the services of Tommy Lee Jones to essay the role.

The itch in Roark's knickers is Dr. Amy Barnes, a geologist. Being a geologist is comfortably one of the most genuinely perilous jobs that one can have while still being excruciatingly boring conversation at a dinner party, a dichotomy which tends to make them peculiarly strident people. Barnes is convinced that the earthquake has caused the formation of a volcano right under the centre of the city. Roark is sympathetic to these concerns, but he can't just start throwing tax payers' money around without evidence. Evidence that Barnes, to her own frustration and no doubt that of the people who have to talk to her at her friends' dinner parties, is unable to gather.

Fortunately, Barnes has a key ally in her quest: Mother Nature. The volcano that she had been predicting to everyone could volcano erupts right under the La Brea tar pits, causing hundreds of dollars worth of damage to the fibreglass mammoths and also pumping boiling lava all over the place. Wilshire Boulevard, traditionally given over to being the main arterial road for the largest city in California, becomes a regular shit show of burning vehicles, stuck underground trains and fifth degree burns. It's a lawsuit waiting to happen. To her credit, Dr. Barnes continues to work for the good of the Angelenos, where most of us would take to the highest vantage point immediately available and look smug.

There are two ways that this sort of film can go: they either deal with a pre-existing adversarial relationship being reconciled in the crucible of extreme circumstance, or the nascent union between two people being thrown together by events. Volcano is the latter and if the sex is as impressive as Roark and Barnes' teamwork, there may yet be further earth tremors in southern California. Using carefully placed detonations of explosive devices, they manage to channel the lava flow through the city's network of subterranean tunnels and into the Pacific Ocean where it would presumably solidify and form a place even drier, hotter and more exclusive than Los Angeles itself, much to the chagrin of the Hollywood elite.

I don't know enough about volcanology to know whether any of this exotic bill of fayre is likely or even possible, but I know enough about disaster films to say that this is a perfectly serviceable one. It ticks all of the traditional generic boxes - relationships are explored and developed, people are roasted to a crisp and the special effects department get to just go nuts - as well as retaining its own personal charm. Volcano gets SIX out of ten Disaster Points.

Thursday 10 March 2016

Disaster Film Olympiad: The Day The Earth Caught Fire

There are two things of which simply no good can ever possibly come: nuclear weapons and the international dateline. When they combine, the overall effect is inevitably catastrophic for all in its path. Unfortunately, these were the precise confluence of circumstances that were to assail the hard-working staff at the offices of The Daily Express in 1961, on a day... THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE!

Typical tabloid hyperbole, that. The Earth did not literally catch fire, but it was nevertheless sickening for something pretty serious. The Day The Earth Caught Fire is an entertaining and considered Cold War fable that warns that the dangers of nuclear weapons - or not checking your calendar - stretch far beyond the obvious. The United States and the Soviet Union, now both building the spiffiest, most powerful hydrogen bombs that modern technology can muster, somehow contrive to each test them simultaneously on opposite ends of the globe without having first checked to see how time zones work. The overall effect throws the Earth off of its normal orbit and into an inevitable collision course with the Sun.

This annoys everybody. The new jaunty tilt of our celestial home causes havoc with the seasons, as drought, heatwaves, storms and floods beset countries quite unprepared to deal with the consequences. The action centres on the newspaper offices of central London, where to call the weather all to cock would barely do the situation justice. The temperature soars, causing a catastrophic drought, ruinously damaging thunderstorms and freak fogs. To be honest, it's pretty similar to what the weather is like in the 21st Century, although it is best to put that thought to the back of your mind since the upshot of all this is: we're doomed. The hardworking Daily Express staffers - motivated by the possibility of a worldwide scoop and powered only by cynicism, lukewarm Coca Cola and a bar tab that looks like Jeremy Hunt's parliamentary expenses claim - do their best to get to the bottom of the story, even though it turns their newspaper into a shrill, weather-obsessed, catastrophe rag. Which obviously could never happen.

It is an unusual disaster film, but it doesn't suffer at all for it: the main characters are reactive, rather than active; resigned rather than rallying. The film neatly captures the constrictive inevitability of a society that has contrived to destroy itself as we all feared it would. There are no heroes, just people being people. Some bad, some mad, but mostly good-hearted. Of course, a film is still always only a film, so a few compromises have to be made: of course our leading man Peter Stenning would take this opportunity to begin a torrid romantic entanglement with Jeannie Craig, a secretary from the Met Office. And naturally he will end up defending her honour from a bunch of feral beatnik water terrorists by engaging in fisticuffs in her apartment. These are things that happen in every film, no matter what the genre or the stakes.

On the whole, however, it is an absorbing and entertaining way to spend 90 minutes. Well, entertaining when one considers the oddly prescient nature of the subject matter: as I watched the film the sky outside was purple and the hail was falling upwards. Particularly pleasing is its ambiguous ending, as the dual forces of science and irony combine to decide the only way to save Earth from a certain fiery demise is to right its place in the heavens with... more atomic blasts. What will happen? The church bell ringers will be putting in for double overtime, if nothing else. It's hard enough ringing bells in normal temperatures and when adequately hydrated. More important still is that I have successfully managed to write the first ever retrospective review of The Day The Earth Caught Fire that doesn't mention it features a pre-super duper super stardom Michael Caine, playing a copper.

More worthy of note even than the revelation that Michael Caine has to eat food and pay his gas bill are the special effects. Considering the technological limitations of the time they stand up very well indeed. Particularly stunning are the vistas of London as a sun-bleached, dried out and abandoned husk - all made by the matte painting mastery of Les Bowie. Film making has become less of an art since computers came along, in many ways. Sigh.

The Day The Earth Caught Fire gets a smouldering EIGHT out of 10 Disaster Points.

|

| For years, man has yearned to destroy the Sun... |

Typical tabloid hyperbole, that. The Earth did not literally catch fire, but it was nevertheless sickening for something pretty serious. The Day The Earth Caught Fire is an entertaining and considered Cold War fable that warns that the dangers of nuclear weapons - or not checking your calendar - stretch far beyond the obvious. The United States and the Soviet Union, now both building the spiffiest, most powerful hydrogen bombs that modern technology can muster, somehow contrive to each test them simultaneously on opposite ends of the globe without having first checked to see how time zones work. The overall effect throws the Earth off of its normal orbit and into an inevitable collision course with the Sun.

This annoys everybody. The new jaunty tilt of our celestial home causes havoc with the seasons, as drought, heatwaves, storms and floods beset countries quite unprepared to deal with the consequences. The action centres on the newspaper offices of central London, where to call the weather all to cock would barely do the situation justice. The temperature soars, causing a catastrophic drought, ruinously damaging thunderstorms and freak fogs. To be honest, it's pretty similar to what the weather is like in the 21st Century, although it is best to put that thought to the back of your mind since the upshot of all this is: we're doomed. The hardworking Daily Express staffers - motivated by the possibility of a worldwide scoop and powered only by cynicism, lukewarm Coca Cola and a bar tab that looks like Jeremy Hunt's parliamentary expenses claim - do their best to get to the bottom of the story, even though it turns their newspaper into a shrill, weather-obsessed, catastrophe rag. Which obviously could never happen.

It is an unusual disaster film, but it doesn't suffer at all for it: the main characters are reactive, rather than active; resigned rather than rallying. The film neatly captures the constrictive inevitability of a society that has contrived to destroy itself as we all feared it would. There are no heroes, just people being people. Some bad, some mad, but mostly good-hearted. Of course, a film is still always only a film, so a few compromises have to be made: of course our leading man Peter Stenning would take this opportunity to begin a torrid romantic entanglement with Jeannie Craig, a secretary from the Met Office. And naturally he will end up defending her honour from a bunch of feral beatnik water terrorists by engaging in fisticuffs in her apartment. These are things that happen in every film, no matter what the genre or the stakes.

On the whole, however, it is an absorbing and entertaining way to spend 90 minutes. Well, entertaining when one considers the oddly prescient nature of the subject matter: as I watched the film the sky outside was purple and the hail was falling upwards. Particularly pleasing is its ambiguous ending, as the dual forces of science and irony combine to decide the only way to save Earth from a certain fiery demise is to right its place in the heavens with... more atomic blasts. What will happen? The church bell ringers will be putting in for double overtime, if nothing else. It's hard enough ringing bells in normal temperatures and when adequately hydrated. More important still is that I have successfully managed to write the first ever retrospective review of The Day The Earth Caught Fire that doesn't mention it features a pre-super duper super stardom Michael Caine, playing a copper.

|

| Daily Express journalist Peter Stenning (Edward Judd) in The Day The Earth Caught Fire: what would Princess Diana do? |

More worthy of note even than the revelation that Michael Caine has to eat food and pay his gas bill are the special effects. Considering the technological limitations of the time they stand up very well indeed. Particularly stunning are the vistas of London as a sun-bleached, dried out and abandoned husk - all made by the matte painting mastery of Les Bowie. Film making has become less of an art since computers came along, in many ways. Sigh.

The Day The Earth Caught Fire gets a smouldering EIGHT out of 10 Disaster Points.

Tuesday 1 March 2016

Disaster Film Olympiad: Flight 90: Disaster on the Potomac

Strange though it may seem, real-life disaster tends not to be a particularly fertile ground for the creation of disaster movies. Reality tends to either be too tame for entertainment or too horrific for imagining, plus it has the unfortunate habit of continually confounding any conventional narrative structure, through its dedication to happenstance and dumb luck. It's more of a challenge to build a decent story arc when historical accuracy dictates that the character you have spent time establishing has a date with destiny at prescribed stage in events. Yet take too many liberties and your film isn't worth a brass farthing: a disaster film can either trade on its creativity or its adherence to reality, there's really no in-between.

Flight 90: Disaster On The Potomac's hands were tied from the beginning. The decision of whose stories to feature has already been taken by history, the ascription of the values that arose from them a done deal. The result is an odd mixture: the preamble is a bit boring, but only in the way that everyday life can be a bit boring. The drama is fraught and tense, but no more so than the historical event on which it is based. Essentially you are left with a compromise: either a news report with additional characterisation or a soap opera with limited dramatic license.

The event on which the film was based took place in Washington DC in January 1982. Air Florida's Flight 90 was scheduled to fly from the capital to Tampa, Florida. The weather was as wintry as a January day in Washington is wont to be, and take off was delayed by an hour and three-quarters due to snow and ice. This was not good news for the real people involved in this incident but its value to the screenwriter cannot be understated: a delay is prime territory for expositional dialogue. Lives are fleshed out and the stakes made abundantly clear. Were I a normal person, I would surely have started to relate to these people, their hopes and dreams.

Unfortunately for everyone involved, the pilots of Flight 90 were inexperienced at dealing with such arctic conditions and their failure to properly de-ice the wings prior to take-off led to the deaths of 74 of the 79 people on board. Their hobbled aeroplane failed to reach adequate speed on the runway, stalled and swiped into the 14th Street Bridge, killing an additional four people stuck on the ground in a snowbound Washington DC traffic jam. The Boeing 737 ended up in the frozen Potomac River below, as though it were nought but a common salmon. The stragglers bob to the surface and their battle for survival begins.

The film is fairly formulaic, cheap and cheesy stuff but it makes a number of key decisions which perhaps raise it above other examples of its type. Most notable amongst these is the fact that the crash itself is not graphically reconstructed: a neat reminder that this is a character piece rather than a Hollywood blockbuster, that each of the characters you are watching was a person you might have bumped into on the street not two years before had life taken a few different turns. The fact that five of the people involved in the accident still were people you could bump into on the street is the film's real point for celebration, rather than any florid displays of special effects mayhem. It's an admirable decision, one which arguably costs the film in terms of its overall effectiveness but saves its soul.

It is not, by any means, a great film. It is not really a good film or a bad film, either. As a faithful account of a traumatic day and as a memorial to the good in humanity that such days tend to reveal, it does pretty much everything that you would assume it should. Flight 90: Disaster On The Potomac gets FIVE out of ten disaster points.

Flight 90: Disaster On The Potomac's hands were tied from the beginning. The decision of whose stories to feature has already been taken by history, the ascription of the values that arose from them a done deal. The result is an odd mixture: the preamble is a bit boring, but only in the way that everyday life can be a bit boring. The drama is fraught and tense, but no more so than the historical event on which it is based. Essentially you are left with a compromise: either a news report with additional characterisation or a soap opera with limited dramatic license.

The event on which the film was based took place in Washington DC in January 1982. Air Florida's Flight 90 was scheduled to fly from the capital to Tampa, Florida. The weather was as wintry as a January day in Washington is wont to be, and take off was delayed by an hour and three-quarters due to snow and ice. This was not good news for the real people involved in this incident but its value to the screenwriter cannot be understated: a delay is prime territory for expositional dialogue. Lives are fleshed out and the stakes made abundantly clear. Were I a normal person, I would surely have started to relate to these people, their hopes and dreams.

Unfortunately for everyone involved, the pilots of Flight 90 were inexperienced at dealing with such arctic conditions and their failure to properly de-ice the wings prior to take-off led to the deaths of 74 of the 79 people on board. Their hobbled aeroplane failed to reach adequate speed on the runway, stalled and swiped into the 14th Street Bridge, killing an additional four people stuck on the ground in a snowbound Washington DC traffic jam. The Boeing 737 ended up in the frozen Potomac River below, as though it were nought but a common salmon. The stragglers bob to the surface and their battle for survival begins.

The film is fairly formulaic, cheap and cheesy stuff but it makes a number of key decisions which perhaps raise it above other examples of its type. Most notable amongst these is the fact that the crash itself is not graphically reconstructed: a neat reminder that this is a character piece rather than a Hollywood blockbuster, that each of the characters you are watching was a person you might have bumped into on the street not two years before had life taken a few different turns. The fact that five of the people involved in the accident still were people you could bump into on the street is the film's real point for celebration, rather than any florid displays of special effects mayhem. It's an admirable decision, one which arguably costs the film in terms of its overall effectiveness but saves its soul.

|

| Alternatively you could forget everything I just said and look at the official movie poster. Cor lummy. |

It is not, by any means, a great film. It is not really a good film or a bad film, either. As a faithful account of a traumatic day and as a memorial to the good in humanity that such days tend to reveal, it does pretty much everything that you would assume it should. Flight 90: Disaster On The Potomac gets FIVE out of ten disaster points.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Attention

You have reached the bottom of the internet