Of course, it is not always this way. Nothing that is possessed of the power of music could always slide by unnoticed and as a result there have been some performances so shattering, so profound and so memorable that they have – directly or otherwise – shaped the course of more or less everything that happened next. This is a fact that is particularly on my mind today, for reasons that I will get into shortly. However, I feel it would be germane at this point to first provide some examples of gigs that sent ripples far beyond their own pond, just in case any of you think that I am lying.

Case study 1: Bob Dylan is so Punk it's unbelievable 1965-1966

One of the curious and unexpected effects of the rise of technology that still threatens to end us all was the re-emergence of the folk music scene in America during the 1950s and 1960s. The apex of this movement was the Newport Folk Festival, an annual three-day analogue happening on the picturesque New England coast; THE place for all the insufferable hairshirt-wearing, hempy draft-dodgers to assemble for a coffee clatch, smoke a doobie and listen to Pete Seeger sing a scurrilous eighteen-verse song about King George II as two shirtless men chop wood at the side of the stage.

Dylan's gig there in 1964 had been greeted by the kind of fervent, rapturous response normally reserved for Jesus Christ on Palm Sunday. Perhaps mindful of what happened to the J man subsequently, the following year the prophet of all of the oakiest folkies decided that the time had come to mix things up a little. On Saturday 24th, Dylan played a three-song acoustic set at an afternoon workshop, accompanied only by his guitar, harmonica and (presumably) two blacksmiths casting pewter tankards, before making the spontaneous and momentous decision to play an electric set the following day to showcase his new material accompanied by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

|

| Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival 1965: Sing while you slave but I just get bored |

This Sunday evening set was completely incendiary. Dylan would again play three songs, but this time his output came courtesy of RAW POWER. He clattered through this truncated set, playing into a wall of discontent and studied outrage, before leaving the stage to a cacophony of jeering and politically appropriate anger. The evening's master of ceremonies Peter Yarrow was left on the verge of tears. Neither in his role as King of the Hippies nor or as Peter from Peter, Paul and Mary had he ever had to deal with such overt and voluble hostility and Yarrow begged Dylan to return to the stage and continue his performance. This he did, unaccompanied once more, cheered to the echo by the same crowd who minutes before had been baying for his blood. An unprepared Dylan didn't have the correct mouth organ and asked the crowd whether or not anyone had an E harmonica. The subsequent volley of metal objects that hurtled towards the stage had been quite unmatched in the area since the Revolutionary War and, now musically replete, Dylan performed two more songs to placate the crowd, whom rock historians by this point may have started to suspect of being a load of reactionary idiots. Dylan wouldn't return to folk music's hallowed spot again until 2002 where, possibly still wary of reprisals from hacky sack-playing beatnik wastrels, he played his set decked out in a wig and false beard.

But it wasn't just American folk fans who had temporarily lost the Zeitgeist: it turned out that British people can be idiots as well, and idiocy without the consoling prospect of the imminent tour of duty in Vietnam is a deadly combination indeed. The following year, during a rambunctiously adversarial European tour, on 17th May 1966 (a Tuesday) Dylan played a concert at the Free Trade Hall, Manchester which would become perhaps the most notorious, bootlegged and discussed non-festival gig ever played in the United Kingdom.

Anyone who believes that trolling is a modern phenomenon that came about with the advent of online communities need only look at the set list from that night in order to see the errors in their thinking. The first half of Dylan's show, solo and accompanied only by himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica, was largely comprised of pared-down versions of his newer material, cribbed from the contentious electric era albums. When he returned for the second half it was in the company of five other musicians, four of whom were on the cusp of finding stardom in their own right as The Band. Here, Dylan played eight more numbers, this time mainly older songs from the folk era but with a thousand volts shoved right up them. The crowd grew increasingly restless, chanting, shouting and slow handclapping their way through the gaps between songs, only for Dylan and his band to beat them back into submission with another wall of noise. The whole affair culminated in the most famous heckle in rock and roll history: “Judas!”, followed by its most famous riposte: a version of Like A Rolling Stone that, as per Dylan's instruction to his group, was played “fucking loud”. Dylan would suffer a serious motorcycle accident two months later and following his recuperation would choose instead to tread a less confrontational path: country rock.

Case study 2: Otis Redding makes black all right for the all whites, 1967

The United States of America's black community had been quietly producing all the music that mattered for generations, only for the rest of the population to ignore it and then have it sold back to them by more "palatable" (i.e. white) British acts for much of the preceding decade. The 1967 Monterrey Pop Festival was when White America finally woke up to this fact and realised they could cut out the middle man and, in turn, help make America great again. The Jimi Hendrix Experience blew a few minds later that weekend (lest we forget that Hendrix himself had needed to leave America and go to the UK in order to gain any recognition as a solo artist, a fact which history has rendered completely absurd), but the standout moment was Otis Redding's set on 17th June 1967, a Saturday. Backed by the Stax Records house band Booker T and the MGs, it culminated in a screaming rendition of Try A Little Tenderness so shattering that it can, even now, still peel the skin from your face. White America, suitably chastened, would never again so wilfully close its ears en masse to the music of their black brethren. This is a considerable legacy for just an hour's work and all suitably marvelled. Unfortunately for Redding, his personal legacy would be cemented by his untimely death in an aeroplane crash just six months later.

Case study 3: James Brown saves Boston

Martin Luther King, one of the great orators and humanitarian figures of the 20th Century was assassinated on April 4th 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. This was a Thursday and by Friday morning, many of America's inner-cities were already counting the cost of a night of protest, anger and civil disobedience. In Boston, MA, the powers that be had a bright idea: if they could get WBGH-TV to film and broadcast the James Brown show scheduled for the night of April 5th at the Boston Garden, perhaps everyone who might otherwise be keeping themselves occupied by rioting would instead be glued to their television sets.

Brown himself took some convincing: he had already signed a contract with a rival TV station for the exclusive filming of a later show in the same tour and if he allowed the Boston gig to be broadcast he would break its non-compete clause, costing him a cool $60,000. No matter: the Boston city government put their hands in their pockets and paid him the difference, in what turned out to be a particularly savvy move for all concerned. Brown's electrifying eleven song set and legendary stage show had the effect that the city council had desired. Having succumbed to riots and fires on Thursday evening, Boston remained calm that Friday night while many other major American cities continued to burn.

All of this is not to say that the whole event was without a frisson of tension, however. In fact, the whole gig was a tinderbox, but one that would be masterfully handled by the hardest working man in showbusiness. The overall effect is completely electrifying, as well as pregnant with a sense of historical significance. In the most famous point in the show, the stage was invaded by over-enthusiastic fans and Brown had to stop the concert in order to prevent the police and venue security from over-reacting in their attempts to make them stand down. Having re-established control and his authority over the situation, Brown would then turn on his audience, admonishing the crowd: “Wait a minute, wait a minute now WAIT!” Brown yelped. “Step down, now, be a gentleman….Now I asked the police to step back, because I think I can get some respect from my own people!”

Case study 4: Jimi Hendrix breaks the national anthem, 1969

As we have previously discussed, Jimi Hendrix had gone to some lengths to get some respect from his own people and at The Woodstock Festival, New York on 18th August 1969 (it was a Monday), he would crystallise his entire experience of race and of national identity down into a single unforgettable moment. With his new band, Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, Hendrix closed the 20th Century's most legendary countercultural gathering with a middling twelve-song set (beginning at the decidedly un-rock'n'roll time of 9 am) that would become infamous for a wailing three-minute long electric guitar rendition of The Star Spangled Banner. Filled with feedback, distortion and notes bent way out of shape by his Stratocaster's tremolo bar, it was viewed by many as a protest - against prevailing racial politics in the US and against its ongoing war in Vietnam - and it caused quite a stir in the United States at large, already a country notably and visibly fractured along generational lines. Hendrix himself later told talk show host Dick Cavett that he didn't consider his performance unorthodox in the least. "I thought it was beautiful". Perhaps it was. Perhaps his tongue was in his cheek. It is a moment frozen in time, whose power to move and shock and provoke is seemingly captured inside the same amber.

|

| David Bowie and friend, 1973. Only one of these men is telling the truth |

Case study 5: David Bowie kills an alien, 1973

Tuesday 3rd July 1973. As his alter-ego Ziggy Stardust, Bowie - a man who craved fame but who just two years previously couldn't even have gotten himself arrested - sent the entire world's youth population into spasms of uncontrollable grief with a spontaneous announcement that this would be "the last show that we ever do". That night, July 3rd 1973 (a Tuesday) Bowie - backed by Mick Ronson, Woody Woodmansey and Trevor Bolder (with additional help from Jeff Beck) - played an extensive seventeen song set, drawing on all his previous album releases as well as covers of songs by both The Velvet Underground and Jacques Brel. The resulting concert entered legend both for Bowie's dramatic announcement of his retirement (actually, he was just off to return to his home planet) and the fact the whole happening was filmed by feted rockumentarian D.A. Pennebaker.

What the anguished teens who were still reeling from the Ziggy-shaped void that had just been ripped into their souls were not to know is how lucky they had been to be getting any of this at all: earlier that day, a notorious gang of Shepherd's Bush herberts had broken in to the Hammersmith Odeon and nicked thousands of pounds worth of high end public address and recording equipment. They were, however, to put it to good use.

Case study 6: Manchester's Big Bang, 1976

At the Lesser Free Trade Hall, Manchester on 4th June 1976 (a Friday), a then little-known group of London herberts (featuring Shepherd's Bush's very own Steve Jones on lead guitar) called the Sex Pistols played to an estimated crowd of as many as 40 people. Such would prove to be the cultural impact of what happened that night, almost everyone who worked in the music industry alive on Earth at the time has subsequently claimed to have been one of them.

|

| Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols, off out shopping |

The Pistols wouldn't achieve their national notoriety until the December 1st that year (Wednesday) when Jones dropped the F-bomb on tea time television. Six months prior, on that night in Manchester the band played thirteen songs, five of which were covers, some indication as to how limited their repertoire still was at this point. The crowd sat transfixed by this clattering, antagonistic and utterly indifferent performance and then staggered out into the world with an urgent need to create their own music. Confirmed attendees that night included Mark E. Smith of The Fall; Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook, Steve Morris and Ian Curtis (later Joy Division and three-quarters of New Order); Pete Shelley, Steve Diggle, John Maher and Howard Devoto of The Buzzcocks; Stephen Morrissey (later of The Smiths, Morrissey and other notoriety); TV producer and future record label impressario Anthony H. Wilson and, yes, Simply Red's and sex with ladies' Mick Hucknall. "It was our Big Bang," Hook would tell the BBC years later. "It created our musical universe". It was, and it did. The course of British culture was definitively and permanently diverted as a result, in ways which can still be seen and felt over forty years later. No-one had even so much as thought to record it, one of rock's greatest oversights.

Case study 7: Radio Ga-Ga, 1985

In 1985, Bob (now Sir Bob) Geldof and Midge (he got an OBE in 2005) Ure (with a smattering of help, no doubt, from Harvey Goldsmith) organised the world's biggest ever charity concert, to raise money for the victims of the brutal, pitiless, civil war and famine in Ethiopia. This became known as Live Aid and took place on 13th July 1985 (which was a Saturday) at both Wembley Stadium in London and the John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, PA. The London gig had been rattling along nicely for six hours and 41 minutes by the time that Queen - a band who, variously, were largely considered to be at the time either all washed up, rock dinosaurs or (rather more troublingly) mercenary shills of the Apartheid regime in South Africa - took to the stage, introduced by comedians Griff Rhys-Jones and Mel Smith dressed as policemen.

They would play six songs in a set lasting just over twenty minutes, including fragments of classic hits Bohemian Rhapsody, We Will Rock You and We Are The Champions, as well as their current single Hammer To Fall. But it was their unremittingly powerful rendition of Radio Ga-Ga that stole the show, no small boast for a show that an estimated FORTY PERCENT OF THE WORLD'S POPULATION was actively engaged in watching. Freddie Mercury's charismatic pull was astonishing to an extent that it has later drawn parallels with the performance of Adolf Hitler at the Nuremburg Rallies in the 1930s. This was perhaps not what the band were aiming for but then Hitler couldn't possibly compete with their record sales, which went through the roof almost immediately. It guaranteed that it this would be another good year all round for the band. And for the starving Africans, of course.

It was, and is, a mesmeric performance, its power to affect quite undimmed by time, its impact still tangible from watching the recording back on YouTube 34 years removed, which I would heartily advise.

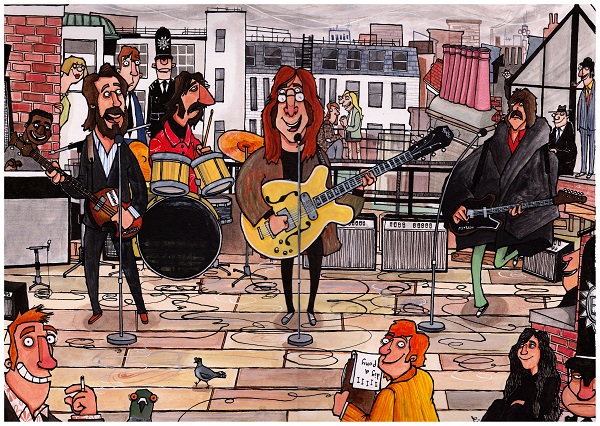

Up on the roof, January 30th 1969

But for all of this: for all of the cultural impact, for all the lives touched and the paths changed, it all pales into insignificance next to an impromptu 42-minute performance in central London fifty years ago today. It is, for me, surely the greatest concert ever played in the history of popular music. The band who gave it played just nine songs. Of these nine, only five were different: one number was repeated on no fewer than three occasions and two others were played twice.

No-one had heard any of these songs before, either: the group eschewed the potential to run through their greatest hits and instead picked all new numbers from a forthcoming LP that wouldn't be released for another 14 months, by which time the band itself had broken up. Two of them were wearing their wife's coat to keep warm in the January air and the gig itself would be curtailed by the intervention of the Metropolitan Police. It was 30th January 1969, a Thursday, on the roof of a terraced office building at number 3 Savile Row, Mayfair. The group in question were The Beatles, accompanied by Billy Preston on an electronic piano. It would be the last time they ever played together in public.

Indeed, this was the first time that The Beatles had performed live ANYWHERE outside of a recording studio for 886 days, since their concert at Candlestick Park, San Francisco on 29th August 1966 (a Monday). For one of their number, it would prove to be the penultimate live performance of a brilliant career: John Lennon would appear before an audience just once more before his untimely death in 1980, once again unbilled, during the encore of an Elton John concert at Madison Square Garden, New York City on 28th November 1974. Which was a Thursday.

The genesis of the idea that led them to the rooftop was a desire to recapture the spirit of live performance after two and a half years of studio-based nurdling, radical experimentation and fierce, circular arguments that had left the group on the brink of dissolution. It stemmed from the death of their manager, Brian Epstein, in the summer of 1967: the group had reinvented the possibilities of popular music but were, from a personal and professional point of view, now completely rudderless. Step forward Paul McCartney, who as the band's new self-appointed leader would spend the remainder of the group's life royally pissing everyone off.

After the backbiting and ill-feeling that had marinaded the recording sessions for The White Album, McCartney had developed the theory that the solution to all of The Beatles problems would be to play live together again just as they had in the olden days, after these lost years of overdubs, tape loops and pissy arguments in windowless rooms. The rest of the band, despite some serious misgivings, went along with this idea if only to shut McCartney up and so the Get Back project was born. McCartney's idea ran as follows: just after the new year in 1969, the band would reconvene at Twickenham film studios to begin rehearsals for their triumphant return to the stage. The songs that they produced would form the basis of this mooted concert at the Royal Albert Hall, as well as being the contents of their next album. In addition, a film crew would accompany the group throughout, making a fly-on-the-wall documentary about how it all came together.

The eventual documentary, Let It Be, was released the following year and portrays four men who had grown apart, going through the motions of being in The Beatles because they didn't yet know any other life. John Lennon spends much of the time huddled in a corner giggling conspiratorially with Yoko Ono and Ringo Starr sits forlornly behind his drum kit, hoping that someone, somewhere, would give him something to do. The sessions were particularly tough on George Harrison, who was the Beatle with the strongest distaste for the return to live performances. Early in the film we watch him get electrocuted twice by a microphone stand, before he receives an equally unwelcome dressing down from the matronly McCartney for his failure to play his guitar parts properly.

Thankfully, what happened next did not make it into the film. On January 10th (a Friday), he and Lennon had a fearsome argument which some reported turned into a physical altercation (although this was later denied by both parties). At issue was Yoko Ono's continued attendance at rehearsals (that old chestnut) and Lennon's strident dismissals of Harrison's new material. At this point, Harrison had flourished as a songwriter – in one scene in the Let It Be film we hear him working his way through the chords for Something – and Lennon and McCartney's continual treatment of his creative output as an afterthought, a mere trifle or good only as album filler was becoming a serious issue. Serious enough, in fact, for Harrison to walk out of Twickenham Studios and announce to the rest of the group he would not be coming back.

Days of mediation followed (although the hard-boiled Lennon's idea was to “just get Eric Clapton in”) and when George agreed to make the Fab Four again it was on the understanding that he would not be a part of any concert, at the Royal Albert Hall or otherwise. George would return to the fold with his friend, keyboard player Billy Preston, in tow. This was a time honoured Harrison trick: bring an outsider with you to recording sessions in the hope it would make the others behave. It worked, too, but McCartney's grand plans seemed to be dead in the water.

Eventually, a compromise solution was agreed where the band would go up onto their office roof and play a set of the material they had been filmed working up, completely unannounced. And so it came to pass that after lunch on January 30th 1969, the Beatles emerged to play in the open air one last time. Many of the staff at Apple Corps would join them to spectate, too, taking a break from their normal day-to-day office activities – chiefly making reverse charge telephone calls to Canberra and smoking ounce after ounce of Moroccan black, according to Ringo Starr's later account of his erstwhile employees' labours.

|

| The Beatles, 3 Savile Row, London; 30th January 1969 (a Thursday) |

The band began their set with Get Back. Now a song about as familiar to everyone in Britain as the National Anthem (they would play this too, incidentally, while the film crew changed the reels in their cameras), at the time it was so shiny new that it probably took anyone in earshot a minute or so to put together exactly what the hell was going on. They soon realised, however, and a genuine cross-section of British society all began to try as best they could to get a better look. In the film, we see excitable secretaries hurling themselves across busy roads, taxi drivers rubbernecking, businessmen who are old enough to have seen everything wearing faces of childlike wonder and, my own personal favourite, an old boy with a bowler hat and umbrella climbing up a ladder on the outside of a building to stand on his own roof and take in the scene with his hands in his raincoat pockets. The Beatles played Get Back twice in succession, with the first of these performances featuring in the final cut of the Let It Be film.

Next up was Don't Let Me Down, and again it was the first of the two performances of John Lennon's new song that afternoon that made it to the final cut of the movie, in spite of the fact that he forgets the words and fluffs a verse mid-way through. Don't Let Me Down would appear on the B side of the Get Back single that April, although it was inexplicably cut from the final Let It Be album by its producer. This would normally represent the biggest dick move of any producer's career, but in this case I think we can make an exception as the culprit in this instance was Phil Spector.

The fourth song of the set was a first of two versions of I've Got A Feeling. In the film, it accompanies a slew of interviews with the spectators who had gathered on the streets below and you can easily, even if you are familiar with the record, miss the fact that the version that appeared on the final album is this live performance. It is a persuasive hint of just how tight The Beatles' playing was that day. Having not played live to anyone in almost a thousand days, on a frigid London rooftop and singing to leaden, empty January skies, here was a band who still had it, never lost it and had sufficient left to just give it away. The next song in the set, One After 909 would also appear on the LP in its live form.

Song six is Dig A Pony. Ringo Starr bellows “hold it!” to halt the introduction because he had been trying to choke down a cheeky cigarette and needed to extinguish it. Lennon, meanwhile, is not confident in his lyrical recall and reads them off book – held in front of him by a lackey no doubt pondering that this will probably be the greatest thing that ever happens to him in his whole life.

By this point, there is considerable commotion in and around the streets of London, as one might expect when the world's greatest rock and roll band play a free concert completely on a whim in the centre of one of the world's great capital cities. Not everyone shares quite the sense of wonder that the whole occasion engenders within me, however. This is, after all, England and English people will always react accordingly. “This type of music is all right in its place and I think it's quite enjoyable,” explains a besuited business type who could be any age from an old 30 to a young 55, “but I think its a bit of an imposition to absolutely disrupt all the business in this area”. As a fellow Englishman, it is hard to argue with him on this point, even though I feel that there need to be exceptions to many a hard and fast rule, particularly if The Beatles are involved. Perhaps he was one of the people who called in the Old Bill to sort it out. Either way, there was by now a growing police presence in Savile Row. They were initially denied entrance to number 3 by the Apple Corps staff, perhaps mindful that the building probably contained all of the drugs in the entire world. However, once the rozzers began threatening arrests for obstruction, uniformed officers slowly began to percolate throughout the building and onto the roof itself.

Still treading the duck boards, The Beatles were by now onto their seventh and eighth numbers of the set, second versions of I've Got A Feeling and Don't Let Me Down. In the latter case, Lennon manages to get the lyrics right and as such a complete live version of the song could later be stitched together and released on Let It Be: Naked. By this point, the powers that be were really rather insistent that the band should stop making this unholy and unexpected racket. Perhaps they were just fed up with all the repetition and could have been placated with a few verses of Ticket To Ride? We'll never know.

Now surrounded by enough police officers to host an FA Cup tie, the band lurched into their final song, the last they would ever play in public together. It was a third performance of Get Back and it is the scuzziest yet, not helped by the fact that the groups' long-suffering personal assistant Mal Evans had been told to turn off the amplifiers by a police officer and, understandably enough, had complied with the instruction. The sound drops out as Lennon and Harrison try to wail on their axe only to get a handful of silence, before both men plug themselves in again on the fly while the song rolls on almost seamlessly. This third version is the one that was released in Anthology 3, complete with McCartney's improvised final verse: “you've been playing on the roof again, and that's no good, your momma doesn't like that, she's going to have you arrested!”. The song concludes hurriedly and is greeted by a loud cheer from Maureen Starkey, Ringo's wife. “I'd like to thank you on behalf of the group and myself and I hope we've passed the audition,” says Lennon to peals of part-sycophantic, part-nervous, part-genuine laughter. The Beatles may not have left the building, but they were no longer on its roof.

In the end, no-one was arrested, a fact made scarcely credible by the sheer quantity of narcotics contained within the Apple building. Perhaps The Beatles had built up enough residual goodwill that the police were willing to turn a blind eye. They had just played a killer gig, after all, and as a passing vicar points out in the finished film, “it's nice to get something for free in this country at the moment...”

However, the long term effects on the group would take their toll. The Get Back sessions had been marred by so much ill-feeling that the album and feature film were shelved, the group instead throwing themselves into recording what would become Abbey Road, a more fitting final hurrah for the band that had changed the course of Western culture forever. On April 10th 1970 (a Friday), Paul McCartney announced that he had left the band and The Beatles were no more. The following month, a Phil Spector-produced rehash of the turbulent Get Back sessions would be released as the Let It Be album, in tandem with a feature film of the same name. Both were hugely successful at the time but have subsequently been reviewed in a far harsher light, unfairly so in my view. There are brilliant moments in each and, although it isn't nice to see it when mummy and daddy fight, they both still love us all the same.

Imagine being there, though. That day in January, now fifty years ago. A moment of history, lovingly recorded so that we can all still be a part of it, unfolding before your very eyes and ears. It must have been hard to fully comprehend the magnitude of what you had witnessed, a process that could only truly begin once it was confirmed that these four brilliant men would never again play together. A process that still isn't over now, as current and future generations still come to grips with what The Beatles did and what they gave us. They were the big bang that created our cultural universe. This was their farewell.